TARANTULA'S BABIES IN THEIR FLYING SAUCERS!: Jonathan Meese, Dennis Tyfus, Tim Brawner

-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is delighted to announce TARANTULA'S BABIES IN THEIR FLYING SAUCERS! an exhibition of recent drawings and paintings by Jonathan Meese, Dennis Tyfus, and Tim Brawner, on view November 5 through December 20, 2025. Together, the three artists present a powerful engagement with culture, mythmaking, and the systemic forces that seek to control and manipulate those narratives. Their work is inscribed, to varying degrees, with the tradition of the grotesque and a fascination not only with the close proximity of desire and disgust, but also the increasingly confusing space between the real and an artificially generated reality. In their own inimitable and darkly comic way, each artist employs elements of the surreal, the fantastic, or the uncanny that speak to the current moment with an uneasy beauty.

Born in Tokyo in 1970, Jonathan Meese moved to Hamburg in the mid-1970s; there, as a young teenager, he began drawing and making collages, influenced and enamored by the books, films, and television shows he voraciously consumed. He later enrolled at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg, where he came under the mentorship of interdisciplinary and conceptual artist Franz Erhard Walther. Meese soon became known for a sprawling and dynamic practice that includes performance, installation, video, sculpture, collage, painting, drawing, set design, libretti, poetry, and artist books—and perhaps even more notorious for his provocative interrogation of recent German history, much like compatriot artist Anselm Kiefer.

Indeed, the mechanisms that enable an authoritarian rise to power remain a critical focus for Meese, along with themes of war, ancient myth, archaic rituals, occult practices, and modern historical figures. His repetitive use of problematic symbols alongside phallic imagery hollows the troubled iconography of its calculated power even as it unsettles the contemporary viewer. These motifs appear alongside references to Meese’s treasured influences: fairy tales, dime novels, the B-movies of Roger Corman, the original Star Trek television series, the films of Stanley Kubrick, the cult classic Zardoz, and Wagner’s Parsifal, which Meese used for an acclaimed 2005 performance and installation.

Within Meese’s diverse and prolific oeuvre, painting is perhaps his most extensive and consistent practice, in which he translates his wild stage presence to a gestural velocity, favoring a maximalist, chaotic aesthetic and text that often jumbles German and English. Film icons such as Scarlett Johannsen, John Wayne, and Vincent Price mingle with mythical references, devilish creatures, military officers, and Meese himself, all carried out in the artist’s distinct faux-naif style, an exuberant rebuttal to the fascist need for control and order. (Even Meese’s own self-styled uniform of a black Adidas track suit confers an endorsement of playful athleticism over strength in service of the military.) Such juxtapositions force us to consider the controlling tools with which we eagerly engage, such as the powerful and far-reaching instruments of media and celebrity that can anoint a movie star as easily as they would help elect a despot.

With a similar multidisciplinary virtuosity, the Antwerp-based artist Dennis Tyfus issues a subtle critique of social convention and systems of power across drawing, painting, sculpture, and installation, as well as the music, performance, zines, tattoos, and ephemera associated with his record label and publishing house Ultra Eczema. A subversive wit connects the various elements of his practice, as in the pseudo-memorial plaque he installed outside his studio building that reads “Here rests Dennis Tyfus” or the installation work “The Inhumane Jukebox” that includes the artist’s off-key acapella renditions of songs by Elton John and Black Sabbath, among others.

Sculptural works have included life-size figures that bear a hyperrealistic resemblance to gallery security guards posed on motorized scooters or chair lifts; the artist likens these static installations to film stills from situations so absurd they couldn’t be conveyed in any other medium. Tyfus’s resistance to order and penchant for the unpredictable is further activated through his “No Choice” works: a “no choice” bar where patrons receive whatever the bartender serves, a “no choice” taxi where riders are subject to the whims of the driver, and a “no choice” tattoo service that affords its customers a similar lack of agency.

Curiously, it is within his drawing practice that Tyfus allows for the least improvisation, carefully planning each dream-like composition before executing it in graphite or colored pencil on paper. (His oil paintings then become venues for more experimentation.) Like Meese, Tyfus is fond of the self-portrait, and he often appears as a character in surrealist situations: an insomniac haunted by apparitions of various fowl and a cat batting at sausage links; a solitary picnicker in a grassy field dotted with giant hams. Working in scale from a modest 30 x 20 cm (about 12 x 8 in) to a more commanding 180 x 130 cm (about 71 x 51 in), Tyfus possesses a wonderful facility for detail that dwells comfortably in both large and small works. Titles contain their own elusive humor (“Appetizer for Destruction,” “Backwards Enlightenment”) and, like the drawings themselves, resist any single interpretation even as they convey a certain poetic seriousness.

Originally from Omaha, Nebraska, the Brooklyn-based artist Tim Brawner shares this controlled approach, rendering his paintings and drawings with an exacting attention to detail and exquisite mark making. Like Meese and Tyfus, Brawner scours the internet and other analog sources for material, collecting it in a “morgue” file of reference imagery he uses to develop drafts of his paintings. Influenced early in his career by masters of dark humor comics like Al Columbia; the films of Paul Verhoeven, Sam Peckinpah, and Takashi Miike; and the stories of H.P. Lovecraft and Thomas Ligotti; Brawner adroitly composes single panels that capture an instant of terror while alluding to a more sinister narrative lurking just outside the frame. Both drawings and paintings exhibit the compositional focus of a film or theater set, with the latter’s close cropping and unusual angles adding to their discomforting voyeurism and atmospheric unease.

Nothing in Brawner’s universe is quite as it should be: a writer struggling at her typewriter displays the wrinkled, macabre flesh reminiscent of Ivan Albright’s subjects; a glamorous female lounging in a luxuriously appointed bed has the nose of a pig; another, the ears of an elf. Much as Grünewald in his Isenheim Altarpiece—and later, George Grosz and Otto Dix in their paintings—ghoulishly distorted subjects in response to social and political turmoil, Brawner points to a certain skepticism and destabilization inherent in late capitalism and, especially, the rapid proliferation of a synthetic aesthetic. He realizes his hyperrealistic scenes using a blend of airbrushing, overpainting, and stippling that occasionally dissolves into glitchy optical confusion: simulacra has overtaken the real. Vivid colors, too, often depart from reality and are taken to the brink of tastefulness in patches of lurid intensity. Facial expressions are central to the work; like Messerschmidt, Brawner is adept at a range of facial theatrics, from the exaggerated grimace, the forced and fanatic laugh, the abject boredom, and even the duplicitous smile of a furry woodland creature.

Drawing equally from an off-kilter pastoral setting and gilded interiors giving way to decay, Brawner’s work seems to teeter uncomfortably between a glamorous, mythical empire in decline and the feral, post-apocalyptic landscapes with all their hidden dangers that follow. Film and television have provided an oversaturation of both types of images in recent decades, helping to inure and numb viewers and hasten a kind of mass anhedonia. And yet as the work of the three artists in this exhibition demonstrate, humans can live amidst darkness and uncertainty and still summon the power to imagine absurd and incomprehensible horrors into something different—something darkly humorous, lyrical, and even beautiful.

– Natalie Weis

-

Installation Views

-

WORKS

-

Jonathan MeeseMEIN LEBENDERZ ERZTENNISSCHLÄGERZ WEINT LEISE FÜR DIE LIEBEN KUNSTPROLLS IM NAMEN MEESIFANTOMASN!, 2024acrylic on canvas

Jonathan MeeseMEIN LEBENDERZ ERZTENNISSCHLÄGERZ WEINT LEISE FÜR DIE LIEBEN KUNSTPROLLS IM NAMEN MEESIFANTOMASN!, 2024acrylic on canvas

39 5/8 x 31 5/8 in (100.5 x 80.3 cm)

framed: 40 3/8 x 32 1/2 in (102.6 x 82.5 cm) -

Jonathan MeeseUntitled (BALTHYS KREUZ), 2000-2001double-sided collage, with acrylic, permanent marker, and mixed media

Jonathan MeeseUntitled (BALTHYS KREUZ), 2000-2001double-sided collage, with acrylic, permanent marker, and mixed media

19 7/8 x 20 3/4 x 3/8 in (50.5 x 52.8 x 1 cm)

framed: 27 1/4 x 24 1/2 x 2 in (69.2 x 62.2 x 5.1 cm) -

Dennis Tyfus'When It Rains, It Power to the People' Collective Housing Project, 2024oil on canvas70 7/8 x 51 1/8 in (180 x 130 cm)

Dennis Tyfus'When It Rains, It Power to the People' Collective Housing Project, 2024oil on canvas70 7/8 x 51 1/8 in (180 x 130 cm)

framed: 71 7/8 x 52 1/8 in (182.6 x 132.2 cm) -

Dennis TyfusDon’t Talk about Them before, during or after a Good Night of Sleep, 2023colored pencil and pigment on paper

Dennis TyfusDon’t Talk about Them before, during or after a Good Night of Sleep, 2023colored pencil and pigment on paper

67 1/8 x 47 1/4 in (170.5 x 120 cm)

framed: 74 3/4 x 55 1/8 in (189.9 x 140 cm) -

Dennis TyfusAppetizer for Destruction, 2025oil on canvas59 x 39 3/8 in (150 x 100 cm)

Dennis TyfusAppetizer for Destruction, 2025oil on canvas59 x 39 3/8 in (150 x 100 cm)

60 x 40 1/8 in (152.4 x 101.9 cm) -

Tim BrawnerMene mene, 2025acrylic on canvas11 x 14 in (27.9 x 35.6 cm)

Tim BrawnerMene mene, 2025acrylic on canvas11 x 14 in (27.9 x 35.6 cm) -

Tim BrawnerWitch, 2025acrylic on canvas60 x 60 in (152.4 x 152.4 cm)

Tim BrawnerWitch, 2025acrylic on canvas60 x 60 in (152.4 x 152.4 cm) -

Dennis TyfusTeenage Witchcraft Convention, 2023graphite and pigment on paper39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (100 x 70 cm)

Dennis TyfusTeenage Witchcraft Convention, 2023graphite and pigment on paper39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (100 x 70 cm)

framed: 43 1/2 x 31 3/4 in (110.5 x 80.5 cm) -

Dennis TyfusHelp (Me Out Here), 2023graphite and pigment on paper39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (100 x 70 cm)

Dennis TyfusHelp (Me Out Here), 2023graphite and pigment on paper39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (100 x 70 cm)

framed: 43 1/2 x 31 3/4 in (110.5 x 80.5 cm) -

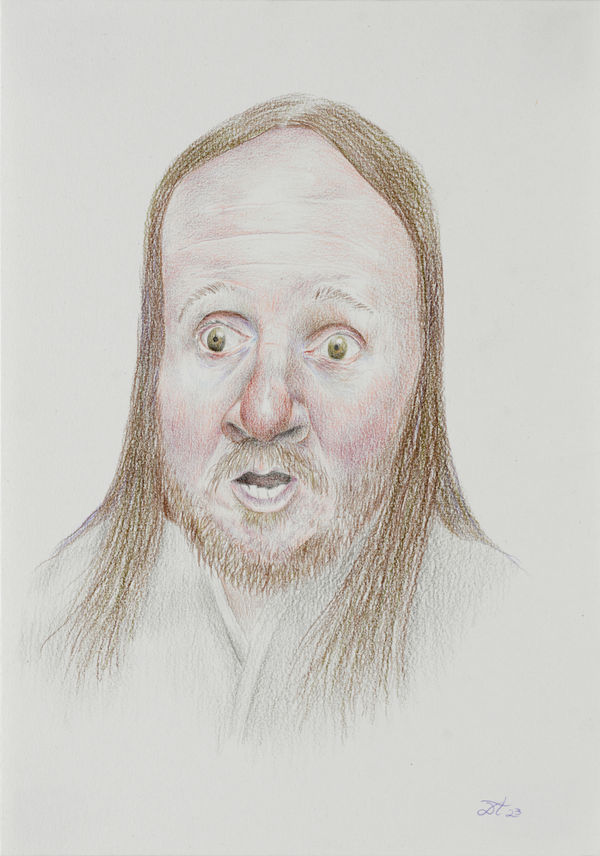

Dennis TyfusThe Germans Are Coming (Danny 8), 2023colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

Dennis TyfusThe Germans Are Coming (Danny 8), 2023colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

framed: 20 3/8 x 17 in (51.8 x 43.2 cm) -

Dennis TyfusSudden Lord (Danny 13), 2023colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

Dennis TyfusSudden Lord (Danny 13), 2023colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

framed: 20 3/8 x 17 in (51.8 x 43.2 cm) -

Dennis TyfusForced To Join The Army (Danny 1),, 2022colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

Dennis TyfusForced To Join The Army (Danny 1),, 2022colored pencil on paper11 3/8 x 8 1/4 in (29 x 21 cm)

framed: 20 3/8 x 17 in (51.8 x 43.2 cm) -

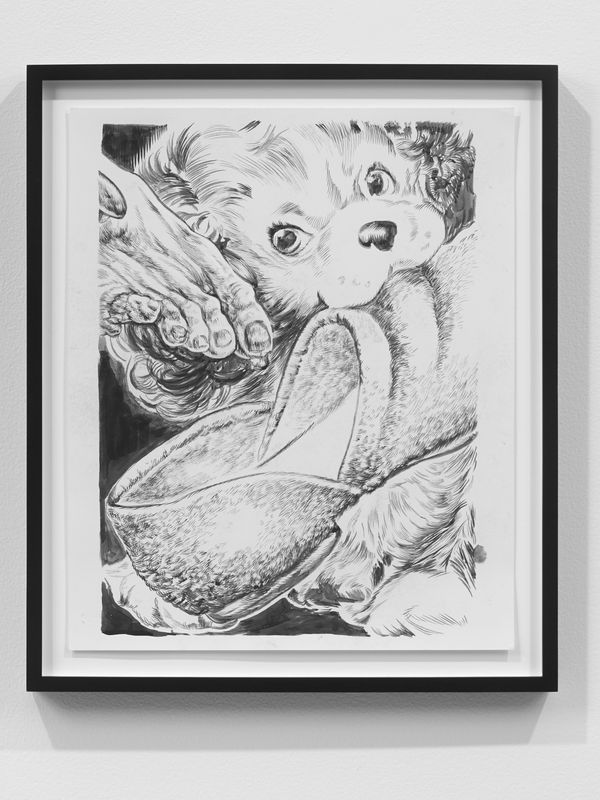

Tim BrawnerIn Escrow, 2025ink on paper

Tim BrawnerIn Escrow, 2025ink on paper

30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

framed: 33 x 25 in (83.8 x 63.5 cm) -

Tim BrawnerTell-All, 2025ink on paper30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Tim BrawnerTell-All, 2025ink on paper30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

framed: 33 x 25 in (83.8 x 63.5 cm) -

Tim BrawnerPinion, 2025ink on paper30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

Tim BrawnerPinion, 2025ink on paper30 x 22 in (76.2 x 55.9 cm)

framed: 33 x 25 in (83.8 x 63.5 cm) -

Jonathan MeeseDR. SELFMEESE XII, 2020pencil on paper

Jonathan MeeseDR. SELFMEESE XII, 2020pencil on paper

16 1/2 x 11 5/8 in (42 x 29.5 cm)

framed: 19 1/4 x 15 1/2 in (48.9 x 39.4 cm) -

Jonathan MeeseDR. SELFMEESE I, 2020pencil on paper16 1/2 x 11 5/8 in (42 x 29.5 cm)

Jonathan MeeseDR. SELFMEESE I, 2020pencil on paper16 1/2 x 11 5/8 in (42 x 29.5 cm)

framed: 19 1/4 x 15 1/2 in (48.9 x 39.4 cm) -

Jonathan MeeseMEINE SAMMLUNG IST KRIEG!, 2025acrylic on nettle47 1/2 x 39 1/2 in (120.5 x 100.3 cm)

Jonathan MeeseMEINE SAMMLUNG IST KRIEG!, 2025acrylic on nettle47 1/2 x 39 1/2 in (120.5 x 100.3 cm)

framed: 48 x 40 in (121.9 x 101.6 cm) -

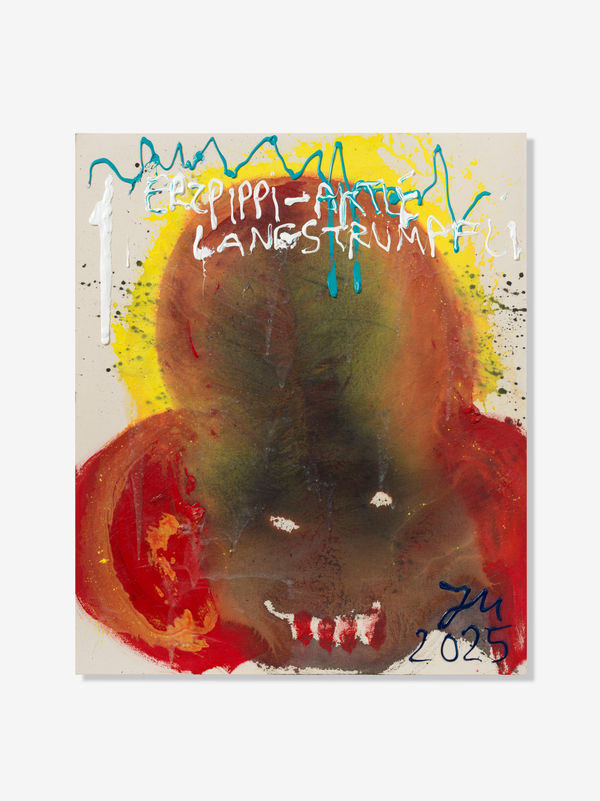

Jonathan MeeseMISS FEUERPIPPI LANGKUNST!, 2025acrylic on coarse untreated cotton cloth47 1/2 x 39 1/2 in (120.5 x 100.3 cm)

Jonathan MeeseMISS FEUERPIPPI LANGKUNST!, 2025acrylic on coarse untreated cotton cloth47 1/2 x 39 1/2 in (120.5 x 100.3 cm)

framed: 48 x 40 in (121.9 x 101.6 cm) -

Tim BrawnerCrystalware and Figure, 2025acrylic on canvas48 x 36 in (121.9 x 91.4 cm)

Tim BrawnerCrystalware and Figure, 2025acrylic on canvas48 x 36 in (121.9 x 91.4 cm) -

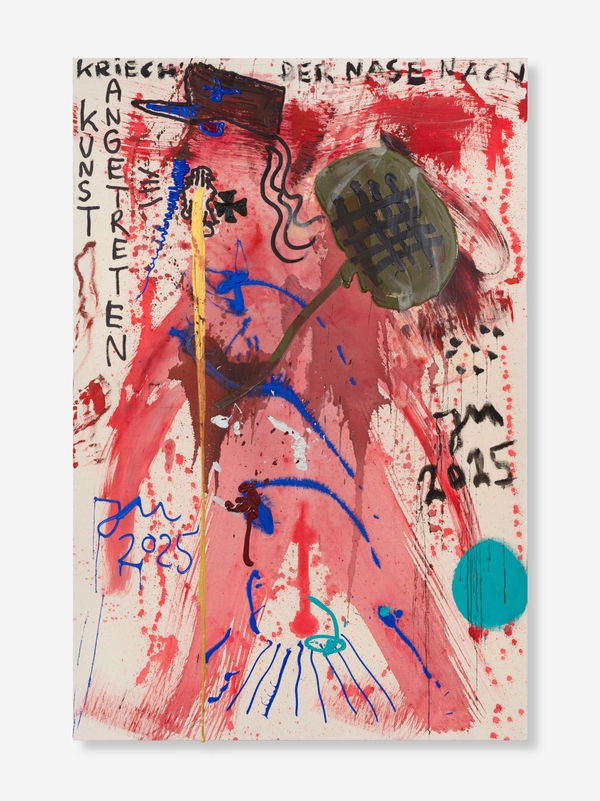

Jonathan MeeseDER TEUFLISCHE KRIEGERZ ENTKRIEGT!, 2025acrylic on canvas

Jonathan MeeseDER TEUFLISCHE KRIEGERZ ENTKRIEGT!, 2025acrylic on canvas

71 x 35 1/2 x 1 1/4 in (180.3 x 90.2 x 3.3 cm)

framed: 71 7/8 x 36 3/8 x 2 1/2 in (182.6 x 92.4 x 6.3 cm) -

Jonathan MeeseDIE TIEFSEE IST AKTIE "KAULQUAPP"! (CASINO "VULKANBLITZ"!), 2024oil and acrylic on canvas71 x 35 1/2 x 1 1/4 in (180.3 x 90.2 x 3.3 cm)

Jonathan MeeseDIE TIEFSEE IST AKTIE "KAULQUAPP"! (CASINO "VULKANBLITZ"!), 2024oil and acrylic on canvas71 x 35 1/2 x 1 1/4 in (180.3 x 90.2 x 3.3 cm)

framed: 71 7/8 x 36 3/8 x 2 1/2 in (182.6 x 92.4 x 6.3 cm)

-

Jonathan MeeseDER KUNST-RABAUKI MEESI !, 2025oil and acrylic on coarse untreated cotton cloth82 7/8 x 55 1/4 in (210.5 x 140.3 cm)

Jonathan MeeseDER KUNST-RABAUKI MEESI !, 2025oil and acrylic on coarse untreated cotton cloth82 7/8 x 55 1/4 in (210.5 x 140.3 cm)

framed: 83 3/4 x 56 1/8 in (212.7 x 142.6 cm) -

Dennis TyfusI Ate Hoevenen and Hoevenen Hates Me, 2023colored pencil on paper

Dennis TyfusI Ate Hoevenen and Hoevenen Hates Me, 2023colored pencil on paper

39 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (100 x 70 cm)

framed: 43 1/2 x 31 3/4 in (110.5 x 80.5 cm) -

Tim BrawnerHamm, 2025ink on paper

Tim BrawnerHamm, 2025ink on paper

17 x 14 in (43.2 x 35.6 cm)

framed: 20 x 16 3/4 in (50.8 x 42.5 cm)

-

-

PRESS

-

The High and Low Heels of Subversion

David Nolan · The Brooklyn Rail December 10, 2025Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels contains a parable about an empire divided between factions distinguished only by the height of their heels. The “high” and “low” heel dispute—a matter of a... -

MUST SEE

Artforum artguide November 3, 2025'TARANTULA'S BABIES IN THEIR FLYING SAUCERS!' at David Nolan Gallery is currently featured on artforum.com’s “Must-See Shows” list, our editors' selection of essential exhibitions worldwide. “Must See” is a feature...

-

-

Artist