DOROTHEA ROCKBURNE: Time Measures Itself

-

Overview

David Nolan Gallery is delighted to present Time Measures Itself, a solo exhibition of new and historical works by Dorothea Rockburne (b. 1929). This is Rockburne’s second solo show at David Nolan Gallery. One of America’s great artists, Rockburne first exhibited at 24 East 81st Street in the early 1970s with Klaus Kertess and his Bykert Gallery. Over half a century later, some of Rockburne’s most seminal pieces return to the same gallery space where they debuted, accompanied by new and recent works. This exhibition offers a unique insight into the development of Rockburne’s practice with industrial materials, underlined by her unwavering dedication to the expansion of artistic thinking.

While attending Black Mountain College in the early 1950s, Rockburne studied with mathematician Max Dehn who introduced her to the principles of set theory, the Golden Ratio, and the knot complement, to name a few. Each of these concepts influenced Rockburne as she explored the possible artistic applications of mathematics. Also at Black Mountain, among friends Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, and Merce Cunningham, there emerged an experimental, neo-avant-garde milieu that was invaluable to Rockburne’s growth as an artist. Found materials were essential to many Black Mountain artists, however Rockburne’s emotional and intellectual visual sense, coupled with an innovative approach to industrial materials and mathematics, continues to set her apart from her peers.

Among Rockburne’s early mathematics-inspired works is 2, 4, 6, 8 (1969/70). First shown at Bykert Gallery in the 1970s, the work consists of four stacked sheets of sequentially cut brown paper joined along their top edge. The forward-most sheet begins at two feet in length, and each subsequent sheet grows in two-foot intervals, concluding with the back-most sheet at eight feet long. Split vertically down the middle, the left side is covered with many layers of dense graphite, while the right is untouched. Rockburne’s combined use of treated and raw material demonstrates the innovative manipulation of everyday industrial elements that became iconic within her oeuvre. 2, 4, 6, 8 also reveals Rockburne’s early interest in set theory that led her to investigations of architecture and geometry in the natural world.

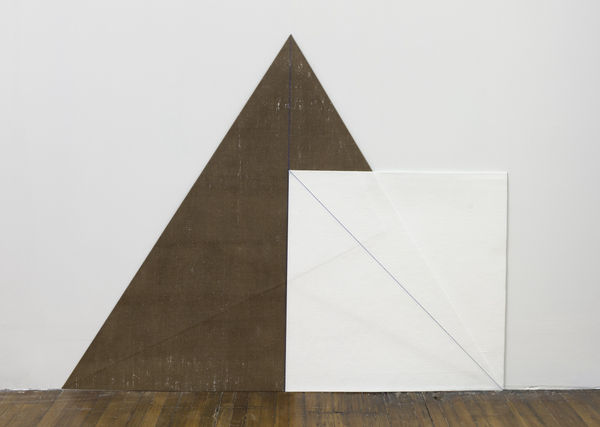

In the mid 1970s, Rockburne developed her series of “Golden Section Paintings”. Golden Section Painting: Square Separated by Parallelogram with Diamond (1974-76), made of chalk, varnish, and gesso on linen, is over five feet tall and eight feet long, one of the largest of its kind. Rockburne’s series of shaped canvases base their structure on ancient Greek theories of proportional interrelationships. Geometrically, the Golden Ratio occurs when a line is divided in such a way that the relationship between the lesser and greater sections equals that of the greater to the whole. “Golden Section Paintings” reconceive geometry as a vast system of proportional interrelationships, as opposed to a series of measurements. This system carries properties that span human existence, linking Rockburne’s work to ancient Greek architects and Renaissance masters, while simultaneously evoking the future and a realm beyond the limits of human knowledge.

A variation of the Golden Ratio is seen in Rockburne’s “Robe Series” from 1974-76. Study for Noli Me Tangere (1976) recalls Italian Renaissance frescoes in its biblical title, geometric structure, and subtle colors. In this work, five muted shades of oil paint are applied to gessoed linen and two configurations of the Golden Square and its accompanying rectangle are combined. The folds of the “Golden Section Paintings” are inspired by topological theories of spatial relationships. Each fold creates a new framework in which the material can associate to itself. Rockburne’s affinity for mathematics is due to transcendent principles such as these, and the physical and philosophical permutations of the Golden Ratio remained a central theme for her in the years that followed.

From 1979-84, Rockburne continued to expand her artistic language of mathematical interrelationships. The “Angel” series includes pieces such as Musician Angel: Parallelogram, Diamond (1979-81) that demonstrate a shift in the artist’s practice. Now working with watercolor on sheets of folded vellum, Rockburne uses color and light to explore the hierarchy of the angels. In applying this system of divine order, she infuses her geometrically rigid works with a newfound spirituality and fluidity that subverts their structural logic.

Recent works in the exhibition contextualize how Rockburne’s understanding of industrial materials has evolved over time. Among these works are a series of five “Brown Paperbag Drawings” (2025). In a kind of symbolic symmetry, Rockburne returns to found, untreated, practical elements to express a career’s worth of ideas regarding mathematics and art. The paper bags are flattened, layered, and mounted to board; they are free of the artist’s signature folds of the 1970s, as geometric systems emerge from the bags’ ready-made creases. Here, Rockburne’s investigations into industrial materials in the second dimension has reached a theoretical height, as the artist has relinquished control to the material’s own internal structure.

Once again using available, ready-made, industrial materials, Infinity (2026/26) was developed concurrently to the “Brown Paperbag Drawings”. Rockburne’s investigations into the second and third dimensions historically inform and complement one another. For this assemblage sculpture, Rockburne combines painted tires with vintage blue oars. The work is held together by two saddle horses from the artist’s studio. At once, the sculpture recalls Marcel Duchamp’s "Readymades", Robert Rauschenberg’s “Combines”, and Italian Arte Povera. Infinity reminds us of the far-reaching relevance of Rockburne’s art.

Time Measures Itself casts a wide net over Rockburne’s career and brings to the forefront her most innovative and influential ideas. Rockburne’s manipulation of industrial materials positions her among the neo-avant-garde who sought to strip everyday objects of their utility and sanctify them as works of art; only at the hands of an artist is such a transformation possible. The continued rigor that Dorothea Rockburne brings to bear on her work and the single-minded focus after five decades remains unrivaled in the twenty-first century.

-

Installation Views

-

Works

-

Dorothea RockburneGolden Section Painting: Square Separated by Parallelogram with Diamond, 1974-76chalk, varnish, and gesso on linen64 1/8 x 104 1/2 in (162.9 x 265.4 cm)

Dorothea RockburneGolden Section Painting: Square Separated by Parallelogram with Diamond, 1974-76chalk, varnish, and gesso on linen64 1/8 x 104 1/2 in (162.9 x 265.4 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneGolden Section Painting: Triangle, Square, 1974chalk, varnish, and gesso on linen54 1/2 x 67 in (138.4 x 170.2 cm)

Dorothea RockburneGolden Section Painting: Triangle, Square, 1974chalk, varnish, and gesso on linen54 1/2 x 67 in (138.4 x 170.2 cm) -

Dorothea Rockburne2, 4, 6, 8, 1969/70graphite on brown paper96 x 72 in (243.8 x 182.9 cm)

Dorothea Rockburne2, 4, 6, 8, 1969/70graphite on brown paper96 x 72 in (243.8 x 182.9 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneMusician Angel: Parallelogram, Diamond, 1979-81watercolor on vellum56 1/8 x 48 1/8 in (142.6 x 122.2 cm)

Dorothea RockburneMusician Angel: Parallelogram, Diamond, 1979-81watercolor on vellum56 1/8 x 48 1/8 in (142.6 x 122.2 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #2, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #2, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

framed: 26 x 33 1/4 in (66 x 84.5 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #3, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #3, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

framed: 26 x 33 1/4 in (66 x 84.5 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #4, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

Dorothea RockburneBrown Paperbag Drawing #4, 2025brown paper bags on paper22 3/4 x 30 in (57.8 x 76.2 cm)

framed: 26 x 33 1/4 in (66 x 84.5 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneStudy for Discourse, 1978colored pencil on vellum34 1/2 x 44 1/2 in (87.6 x 113 cm)

Dorothea RockburneStudy for Discourse, 1978colored pencil on vellum34 1/2 x 44 1/2 in (87.6 x 113 cm) -

Dorothea RockburneInfinity, 2025/26vintage oars, painted tires, saddle horses, wood, and bricks93 x 40 1/2 x 60 in (236.2 x 102.9 x 152.4 cm)

Dorothea RockburneInfinity, 2025/26vintage oars, painted tires, saddle horses, wood, and bricks93 x 40 1/2 x 60 in (236.2 x 102.9 x 152.4 cm)

-

-

Artist